It is perhaps unfair to compare and contrast the work that goes into growing Pinot Noir with that applied to other varietals, but that is exactly what I intend to do here.

The only time I don’t wake up thinking about Pinot Noir is the short window of time between bottling day (early April) and budbreak (late April) – a most joyous stretch that I cherish akin to The Masters each Spring. The other 11 months and change can only be described as an all out battle of wills that would provide a fitting test for even the “Tiger Woods” of grape growers. For the record, I’ve had my share of Greg Norman-esque collapses through the years.

In the Lowrey Vineyard, the cycle begins in December with the first pruning cuts of the season. Traditionally, we opt to prune our old Pinot block first each winter, as the vines usually winterize and harden off earlier than our other varietals. Excess wood is trimmed away from the vine until we are left with four canes to choose from, each housing 8-10 buds. Two of those four canes will be tied down and two left as insurance, to be removed after a successful budbreak in Spring.

Budbreak is always a nervous time, especially in early awakening varietals like Pinot Noir and Pinot Gris. Minor frost damage is usually inevitable, so it becomes more about avoiding the killer frost. Windmills can be handy in this pursuit, but they are not the magic shield that they are sometimes made out to be.

Once the frost worries subside, the real fun begins. I would estimate that I average at least a couple of hours each day through the growing season tending to Pinot Noir. It is at this point where every vine becomes a puzzle that needs to be solved, but with a solution that is constantly evolving based on the conditions. Pinot Noir vines grow very vigorously, and it is easy to get behind in taming the growth should you get complacent. Recent research has shed light on the benefits of early season basal leaf removal in berry set of Pinot Noir, so that is now a focal point along with regular thinning practices. The ultimate goal is establishing proper shoot spacing, cluster load and berry set prior to bloom phase.

As the canopy takes shape, the bloom through veraison stage shifts focus to disease prevention and maintenance. Depending on the day, I might be tinkering with shoot positioning, removing leaves, cluster thinning or hedging. Although all varietals have need of these jobs in varying degrees, no varietal demands the attention to detail required in Pinot Noir. It is reflected in the make or break nature of Pinot, which is certainly not for the faint of heart. I may have alluded to this once or twice over the years.

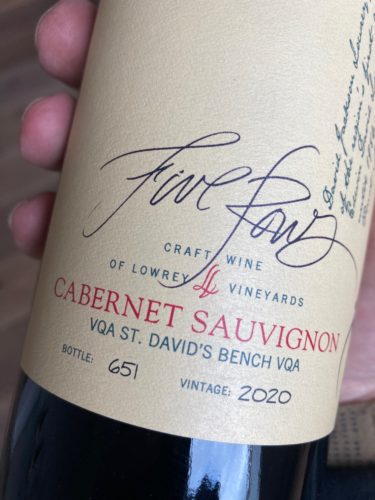

The “easy” stage of Pinot growing ends abruptly, as the berries fully colour up and start to accumulate enough sugar to entice a shocking number of pests to have a taste. It is a time when the tightness of the cluster, and any trapped debris within, can pose a potential threat of Botrytis. It is important to be especially vigilant with both your eyes and nose when walking through the vineyard on the hunt for any signs of rot. If found, the offending clusters are removed promptly to prevent disease spread via fruit flies. This constant daily search for rot can take a mental toll, so I make sure to break up my days by working in easier varietals like Cabernet Sauvignon.

The final gauntlet of Pinot Noir growing revolves around when to harvest the crop. I’ve written about this agonizing decision many times in the past, but there are so many variables at play it doesn’t hurt to review. Every vintage presents a new set of parameters that you must adapt to: cluster tightness, skin thickness, crop load, weather conditions, disease pressure, seed ripeness, flavour development, berry composition (sugars and acids) and stem ripeness (should you choose to include whole clusters in your fermentations).

Once a picking date is settled upon, or more likely forces itself upon you, we now enter the thorough Pinot Noir sorting process. Ours is three stage: a walkthrough visual inspection of every cluster in the rows we choose to harvest, a second closer inspection of each cluster by the hand-picking crew and, finally, a third rotten berry inspection en route to the destemmer. Only then can I feel confident that the fruit we’ve worked so hard to keep clean and ripen is fit to be vinified.

The 2020 vintage was characterized by an early budbreak and some long stretches of the hot and dry conditions that winemakers dream about. There were the usual challenges (detailed above), but ultimately the fruit came in ripe and beautiful on September 18th (21.6 degrees Brix, 7.0 g/L TA). Our fruit was harvested from rows 2-5 of our oldest vines and rows 8 and 15 from the slightly younger plantings. Whole clusters were added to two separate bins (10%) and then filled with destemmed berries (90%). The clean fruit was allowed to soak in the bins for seven days before natural fermentation began.

Fermentations were punched down by hand three times daily, reached a peak temperature of 30C, and were dry after seven days. The new wines were pressed after a five-day post ferment maceration. Five French oak barrels were filled (20% new oak) and allowed to undergo malolactic fermentation over the next couple of months. The wine spent 24 months in oak before bottling 122 cases on April 6th, 2023.

I am in love with this Pinot Noir right now, mainly due to its striking aromatics of ripe cherry, black currant jam and truffle/mushroom. It is very tempting to advise enjoying it now, but I’m sure it will evolve and improve over the next few years. If you like a Pinot that exhibits a bit of youthful tannin, then by all means give it a go!